I.

I was at a conference last week, one which was ostensibly about the cybersecurity industry in Canada but, perhaps by dint of that very fact, couldn’t help but actually be about two other, tangibly-related things:

1/ the year we’ve had in this country, re: America’s collapse into autocracy (which I’ll not be thinking about today); and

2/ the threats of A.I., which — in the year since the last such cybersecurity conference — have ballooned from “this sure is on the horizon!” to “this is part of everything we do and we still don’t know enough about what it’s doing.”

One of the speakers was at pains to note that most of what we broadly call “A.I.” is still, in one form or another, only “next-word prediction.” This is good for us all to keep in mind as we continue to use “A.I.” to describe what is just fancy predictive text, the kind that has been sticking its thumb in your iMessages or Google Documents for a decade now, telling you what it thinks you’re about to say.

I find it subtly charming that, in terms of predictive text, we were predicting the wrong text when we, humans, plopped “A.I.” into the hole that was created when generative algorithms started being Wall Street’s favourite thing. That’s neat, and fairly interesting: it’s not A.I., but “A.I.” seemed like the right word to everyone at the time (no doubt goosed substantially by bad-faith actors in the technology sector aiming for a valuation), so we stuck with the term, and here we are.

So: A.I. is next-word prediction. The words might not actually be words, per se, depending on the use case. They might be the pixels in a slop image of an evil bowl of soup; or they might be the “painterly” sky in the background of a “photorealistic” video (those two words in quotes are mutually exclusive, but I digress).

Nevertheless, the results are the same. Those predicted units of information are just what the computer expects to see in the blank space, based on all the contextual data of what else has appeared in that blank space, before. The machine is just guessing what a person would write or draw or film, if it were a person doing it, and not the machine.

So here, we come to another thing I find charming in all this:

A good-sized portion of people are looking at A.I. slop, and (for the most part) finding it noxious. It looks silly; it sounds fake; it tells you how to kill yourself or just suggests that you should; etc. Basically: it’s bad.

Theoretically on a long enough timescale this will cease to be the case, because the models will either develop sufficiently to overcome their current limitations, or the large mass of us will become contextually illiterate and will stop noticing the problems.

But in the meantime, here’s the charm (for me): humans are pattern recognition machines. It’s the hidden masterstroke of our entire psychology; it’s the heuristic that lets us discard, say, 99% of the visual data in front of us and send an adrenaline spike near-instantaneously to our heart, because a sabre-tooth tiger is running towards us. Our facility for pattern recognition is what’s kept us alive; it might be the thing let us survive long enough to become human beings in the first place.

And yet when many of us look at A.I. slop — which is a pattern recognition output — we don’t recognize the pattern. Or more likely, we recognize just enough of the pattern to recognize that the pattern is wrong, and that whatever has been spat at us by the algorithm is buried deeply in the uncanny valley.

What, then, is the missing piece? Where is the ghost that has clearly not (yet) been embedded in the machine?

Per that bluesky post above, it’s equally interesting that there are (I assume) whole tranches of people who look at A.I. slop and aren’t just able to recognize the pattern, but actually level the pattern up and say “holy shit, this machine is smart.” Which is a rather lovely, solipsistic little human foible. “Wow, this thing reminds me so much of me that it must be as smart as me!” (The punchline is inherent in that one, I think.)

II.

Here’s something about perception, unrelated to A.I. except broadly:

This gets at something that might apply to the above, i.e. that mechanically, our human pattern recognition software requires certain perceptual triggers in order to interpret something as real.

Moreover, it gets at something else — and it might be the particular something else that has been my personal brainworm for the last several months — in its discussion of the haptics of cinema. The video points out that while we can start with the idea that vision can be a physical sensation as well as an optical one, doing so is only the first rung of a ladder that can extend down into a consideration of the total physical sensation of watching a film (or, I’m sure, encountering any piece of human expression).

There is a great, uncharted something else there, is my point, which deserves further study.

Let’s check in with our old pal Rian Johnson again. Johnson recently took his own firm stance on A.I.:

“Fuck AI. It’s something that’s making everything worse in every single way — I don’t get it,” Johnson says. “I mean, I get it in a ‘This makes sense to save money by not paying artists’ way.’ But then, what the fuck are we doing? Is this where we want to be?”

“Is this where we want to be?” is the part of the equation that drives me, too, a bit batty; but it’s not really central to my thoughts today. (But while we’re here — perhaps extending some of my civic ideas last week into the art space — is this the world we want to imagine for ourselves? The one where computers spit our own pre-chewed food back into our mouths, until most people neither notice nor care?)

But I have once again digressed. What I really wanted to say about Rian Johnson was: the quote above comes from his press tour on the new Knives Out movie, Wake Up Dead Man, and I have spent the fall eagerly, giddily awaiting that movie’s arrival on Netflix next month, so that I can watch it a second time. This is not because it’s a great movie (though it is) or because I want to experience the whole story again (although I do).

It’s because there are a handful of shots in the movie in which the lighting in the church — which, within the diegesis, is presumably the sun outside the church, emerging from behind a cloud; or the reverse, and then filtering itself through church windows that are either clear or stained glass, depending on the angle — changes dramatically over the course of dialogue scenes between Benoit Blanc and Father Jud Duplenticy, as they discuss matters of faith.

I’m shivering just typing the words. How’s that for a haptic realism: the hairs on my arms are up right now, thinking back on the way those shots made me feel.

Here we have layers within layers. Jud and Blanc are discussing faith, the ne plus ultra of “is there something there, something more than what we can measure?” Is there a ghost in the machine? I’m sitting here having a visceral reaction recalling a piece of cinema, something that is mechanically constructed from countless pieces of real-world craft, and yet — when they all work together — conveys something else that is both intrinsic and extrinsic to its nature.

III.

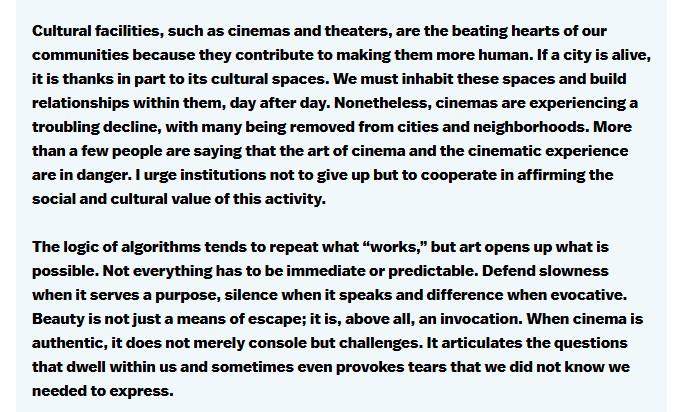

On that subject, what if we turn to no less an authority than the pope:

I am no Catholic, and I will never be a theist. But I’m really starting to like that pope.

I mentioned that the something else has been my particular brainworm, these last few months. This is an interest less in, say, matters of faith than what I would call matters of the spirit. I recently cracked open the draft of my first novel again and did a fairly substantive rewrite; this novel began, you might (or more likely do not) recall, as an exercise in following my own inner voice wherever she wanted to take me, which didn’t just result in a book, but an answer to a gender-identity riddle four decades old, and the healing of buried trauma so spiky I kinda cannot believe it was possible to bury it.

That experience has, in the years since Enneaka‘s first draft, led me to wonder more and more: what is that voice? What is that spirit?

I may not be a theist, but I am a Buddhist, and my practice has led me to work with a sangha that is both interested in matters of Buddhist principle and, to a lesser degree, in the creative process. This is useful to me. We write together once a month, for long stretches; and our teacher is, herself, a writer; and writing and reading come up a lot in any given discussion amongst our group in any given week.

Most importantly, the process of writing has become part of the instruction, as regards the placing of attention.

Our teacher, Susan, feels this connection very strongly: whenever we write or undertake any creative art form, we’re placing our attention on something. This connects to meditation because when we practice meditation we’re placing our attention (in our practice, anyway) on breath; if I told you right now to place your attention on your left knee, you feel something move there. Strengthening this ability to place attention can only help us place it on the something that we follow when we are writing, painting, dancing, or anything else.

But the something, the spirit, that we follow with our attention while creating something that has not existed before… what is it?

Well, for one thing: it’s obviously whatever’s missing from whatever next-word-prediction text the A.I.s are spitting at us. And maybe it will always be missing.

Then again, maybe not. One of the reasons our choice of terminology for A.I. is important is because — like “fake news” before the Big Orange Meanie corrupted the term to serve his political/financial ends — A.I. is a real thing that bears real discussion and consequential action. Calling next-word prediction “A.I.” blunts our ability to have conversations about actual artificial intelligence.

But, for example, if we ever actually do manage to arrive at Artificial General Intelligence, we are going to have to have a conversation about whether the spirit can exist within that machine. If it does, that’s gonna be a big, galaxy-breaking deal — a change in how we think about consciousness, generally; and our own consciousness, intention, spirit, particularly.

Or, to put it as one of my old pals put it,

“We have all been dancing around the basic issue: does Data have a soul? I don’t know that he has. I don’t know that I have. But I have got to give him the freedom to explore that question himself.”

Until then, another end-note: my revision of Enneaka has in large part been to strengthen some of these matters of the spirit as it applies to the book itself. All of what I’ve written about above wasn’t just the process of writing this novel; it’s intrinsic to the story, as well. So as you can imagine: it’s been on my mind.

And what a lovely thing, that imagination is. You can sit where you’re sitting and read about me shivering as I think about Wake Up Dead Man‘s church-lighting effects, and even if you can’t feel them with me, you can conjure an image that is made of nothing besides our shared experiences of being human.

This most recent revision of Enneaka has also, I should note, gone in tandem with reading the final volume of the Book of Dust by Philip Pullman, which greatly concerns the relationship between the intentions of the universe and the imagination of its inhabitants, directly. The spirit, you could say. So all of this wraps together, to me.

I may have more to say on The Rose Field and Dust and the imagination sometime, but until then I will allow: I believe in the reality of that spirit, utterly. It moves me. It opens a lot of possibilities that the lazier version of my atheism would have denied me, earlier in my life.

As for what we currently call A.I., the spirit answers Rian Johnson’s question above firmly: no. We do not want to live in a world given over to next-word prediction. I imagine that might extend as far as “stop being dickheads generally and let’s get back to making things that are new and vital and human,” but I’m a mite biased.

Regardless: this answer might be enough to save us from all the machines grinding us down. If it’s not, let it serve as our human credential to those after us: while we were here, we really were.